Kabir Taneja

China’s much talked about One Belt One Road or OBOR initiative is causing some unease in the power corridors of New Delhi as Beijing’s ambitious $1 trillion project starts to take shape.

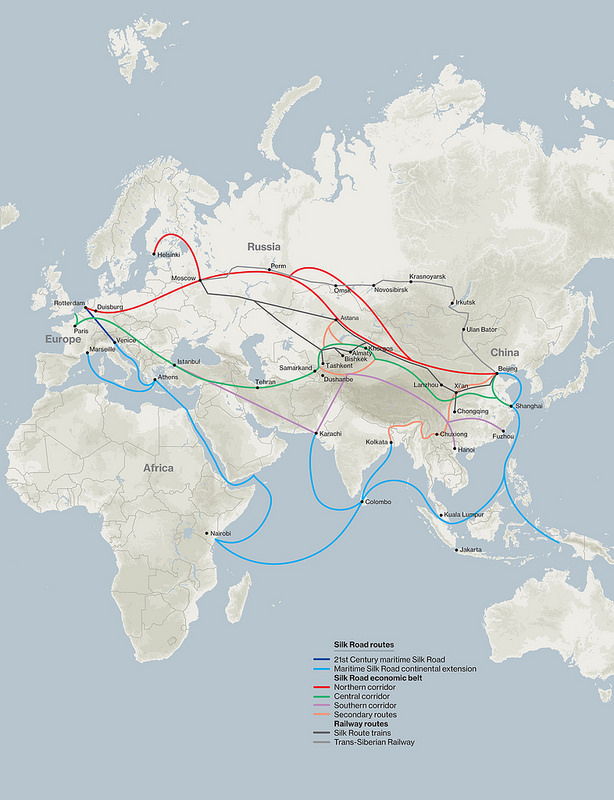

Announced in 2013 by Chinese president Xi Jinping, the OBOR project, which will bolster China’s economic and geopolitical footprint, has challenged India on two fronts – the first in the form of large Chinese investments announced for Pakistan, and second, a fast increasing strategic and economic presence in the Indian Ocean. This includes Chinese money being pumped into port projects in neighbouring countries like Sri Lanka and Bangladesh.

India’s concerns

Other than the natural instinct of such a huge capital building initiative by an adversary in the region, the main point of contention for India is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor or CPEC, which is also part of OBOR. The port of Gwadar, not far from Karachi, where the Arabian Sea meets the Persian Gulf, is today completely handled by China. Both Islamabad and Beijing announced $46 billion developmental programmes that included Chinese money being pumped into Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, which in effect cements the strategic ties between the two nations even further.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor’s mandate includes the development of energy infrastructure, roads and railways. Its influence ends in Gwadar, which is fast becoming a de facto Chinese staging post in the Persian Gulf area.

The development of more projects such as Gwadar could significantly trouble India’s current dominance in its backyard – the Indian Ocean region. External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj said in May 2015 that Prime Minister Narendra Modi, during his visit to China, had “very strongly” raised the issue of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor going through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. This, along with China’s growing clout in the Indian Ocean, remain the two main concern spots for New Delhi to give any sort of precedence to OBOR in its own foreign policy narrative.

Last week, reports surfaced suggesting that troops from China’s People’s Liberation Army had been sighted on the other side of the Line of Control in Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir. It is being suggested that the Chinese troops are there to build infrastructure to protect and aid commercial Chinese projects. Similar reports had surfaced last year as well. For New Delhi, OBOR may be a potential economic opportunity but it also threatens India’s interests. India’s former foreign secretary Shyam Saran recently wrote that if China indeed succeeded in the economic and geopolitical aims behind OBOR, India may get “consigned to the margins of both land and maritime Asia.”

China’s vision

As of today, OBOR is perhaps the biggest programme for China. It is a huge undertaking with an ambitious plan to connect major Eurasian economies using tools of infrastructure development, facilitation of trade, infusion of big investments in areas such as road and rail development, oil and gas and special economic zones.

The bedrock of the OBOR programmes is rooted in two historical trade routes, with the first being the ancient Silk Road that traversed through the central Asian region, peaking during the period of China’s Tang Dynasty (618 CE-906 CE). The second is the Maritime Silk Route, sketched roughly on historical Chinese maritime trade routes through the South China Sea and beyond, touching as far as East Africa and Mediterranean Europe via ports such as Kolkata, Colombo and Karachi in South Asia.

Funding for OBOR, which is now one of the world’s largest inclusive international development initiatives, is supposed to come via a host of financial initiatives by Chinese institutions. The much-touted Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank that was proposed on the sidelines of the OBOR project itself in 2013, for which India is a founding member, is pitching to invest a big part of its $100 billion corpus to OBOR-related activities. In May last year, it was reported that the China Development Bank separately is preparing to invest more than $890 billion for over 900 projects involving 60 countries as part of the belt over a 15-year time frame. The sheer magnitude of OBOR is something that puts India’s own interests at significant unease, while having no counter to offer for it.